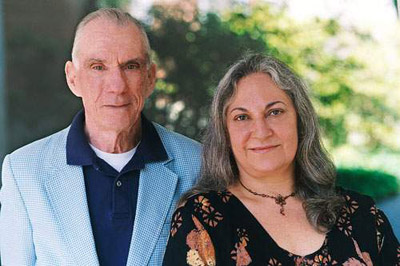

Canadian historian Christopher Laursen recognizes the efforts of Dr. Robert Jahn, Brenda Dunne and supporters of the Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research (PEAR) for delving into issues of consciousness over the past 28 years. PEAR is closed its doors in February 2007.

Early in 2007, the founder of Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research (PEAR) announced that the famous and controversial lab would be closing its doors. Opened in 1979 by jet propulsion scientist Dr. Robert G. Jahn, at the time Princeton University's Dean of the School of Engineering and Applied Science, PEAR developed tests which brought forth intriguing results with respect to extrasensory perception, in particular remote viewing and the ability for the human mind to affect machines.

"Since that time, an interdisciplinary staff of engineers, physicists, psychologists, and humanists has been conducting a comprehensive agenda of experiments and developing complementary theoretical models to enable better understanding of the role of consciousness in the establishment of physical reality," PEAR's website states.

"The one interface that hadn't really been explored was that of psychology - the human mind," Dr. Jahn told the Princeton Alumni Weekly about the origins of PEAR last November. "What could engineering utilize, in terms of basic knowledge of how the mind works?" That's what PEAR, led by Dr. Jahn and managed by developmental psychologist Brenda Dunne, set out to do. Dunne offered a counterpoint to Jahn's scientific inventions, providing "the more metaphysical and subjective understanding of the material to bolster Jahn's largely analytical approach," wrote journalist Lynne McTaggart in her 2002 book The Field. "He would design the machines; she would design the look and feel of the experiments. He would represent PEAR's face to the world; she would represent a less formidable face to its participants."

Dr. Jahn, now 76 years old, is resolute in his decision to close the long-standing project and encourages researchers to push these studies further. He told the New York Times, "For 28 years, we've done what we wanted to do, and there's no reason to stay and generate more of the same data. If people don't believe us after all the results we've produced, then they never will." The project has stood under the shadow of constant criticism, much of which has been aired over the past few weeks in the press coverage of PEAR's closure. But such comments do not serve as a "final knife in the back" of a program that has contributed a great deal to a new frontier in science, psychology and understanding our world.

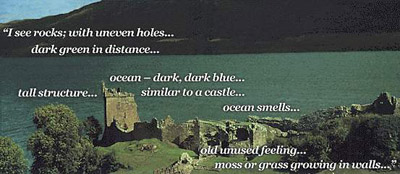

For example, in the 1980s, Dr. Jahn and his team greatly improved the protocols for remote viewing experiments, which he aptly calls remote perception. In his book The Reality of the Paranormal (London: Guild Publishing, 1988), past-president of the Society of Psychical Research Arthur Ellison described the experiment as follows: "The agent photographs the target and writes a description of it, but also ticks off answers to thirty binary questions serving to define the target in a particular code (is it indoors or outdoors? Noisy or quiet? Are there cars or no cars? Is there water present or not? and so on).... The perceptions are acquired and the data sheet completed hours or days before the target is visit, or, in most cases, before it is even selected." Binary coding of elements of the image photographed enabled computer analysis of what was perceived by those participating in the remote perception experiments.

One of the famous results of this experiment was the target photograph of the ruins of Urquardt Castle on Loch Ness, Scotland. The remote perception written down is illustrated in the below photograph from PEAR's website. "How the consciousness of a percipient can get access to points remote in time and space from the current location is well beyond our physical understanding," Dr. Jahn told Ellison.

This is but one of PEAR's many experiments which are fully detailed on the lab's website, in journals, books and magazine articles. The Princeton Alumni Weekly reported: "Jahn's general conclusions are that anomalous phenomena are real, can be studied scientifically in large data sets, and could be used in applications. He admitted that some of his faculty colleagues view the research with scepticism, and others have been completely dismissive. But he does not think that the engineering anomalies work affected his reputation as a distinguished researcher in electric and plasma propulsion."

PEAR's opponents have, not surprisingly, included members of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (formerly CSICOP) and academics such as University of Maryland physicist Robert L. Park, author of Voodoo Science: The Road From Foolishness to Fraud. Park told the New York Times, "It's been an embarrassment to science, and I think an embarrassment for Princeton. Science has a substantial amount of credibility, but this is the kind of thing that squanders it."

Such comments, in my opinion, are very narrow-minded. Science, by definition, is knowledge founded through objective principles involving systemized observation of and experiment with phenomena. That definition works up to a point. But what about comprehending things outside of the material world? Science can readily explain many things in our physical world, but why exclude it from observing the non-physical world, including phenomena related to consciousness? Think of what would not have been accomplished in humanity if people didn't try to understand the invisible, so to speak! If you look back at pretty much all of great thinkers who theorized about the non-material world, they too received a great deal of harsh criticism, yet their work forms the basis of today's commonly accepted scientific understanding - and offers a foundation upon which our knowledge can expand.

The value in projects such as PEAR is uncovering new possibilities in the human mind, our world and our universe - and attempting to do so as objectively as possible. In the world of academia, even where "pure" science is concerned, there is never any waste in exploring speculative thought, especially when it is trying to explain documented human experiences, such as precognition, extrasensory perception or witnessing things that fall outside of everyday understanding. Science is rooted in speculation.

Dr. Jahn and his colleagues have dedicated a great deal of time contributing to a worthy venture. Their dedication has encouraged significant support over the years for PEAR. James S. McDonnell, co-founder of the McDonnell Douglas Corporation, was the first donor, encouraging others, including philanthropist Laurance Rockefeller, to invest a total of over $10 million US into consciousness research since 1979, enough to sustain a small staff and a develop variety of intriguing equipment with which participants could mentally interact. It always has been a good idea, and like any experiment, forms the foundation for future work.

"It's time for a new era," Dr. Jahn said in the New York Times, "for someone to figure out what the implications of our results are for human culture, for future study, and - if the findings are correct - what they say about our basic scientific attitude."

Further reading:

Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research (PEAR): http://www.princeton.edu/~pear/

There are about 50 downloadable papers on the Publications page. Brenda Dunne recommends one entitled "The PEAR Proposition" which offers a comprehensive overview of the history and accomplishments of the program. There is also a 520-minute DVD/CD set available by the same name for those who want a more intimate experience of the laboratory.

Lynne McTaggart. The Field: The Quest for the Secret Force of the Universe. New York: HarperCollins, 2002.

"Mind May Affect Machines" by Kim Zetter in Wired magazine, 19 July 2005: http://www.wired.com/news/technology/0,1282,68216,00.html

"A Princeton Lab on ESP Plans to Close Its Doors" by Benedict Carey, New York Times, 10 February 2007.

Image Credits:

Photos of Urquardt Castle and of Dr. Robert Jahn and Brenda Dunne courtesy of Brenda Dunne, PEAR.